In Simon Raymonde’s autobiography “In One Ear: Cocteau Twins, Ivor and Me,” the development of post-punk music and culture in the late ’70s and early ’80s into what would become known as “alternative” serves as the backdrop as the writer gets an autograph from David Bowie, secreted on a platform at the back of a London club, on his way to becoming a member of a genre-defining band whose landlord happened to be Pete Townshend.

For Raymonde, it’s not an exercise in namedropping or even telling all about Cocteau Twins (there is a lot of that, though), the mysterious shoegaze pioneers. Fans of the UK band will relish the inside stories of band dynamics between Robin Guthrie and Elizabeth Fraser, a couple, and Raymonde, who joined on bass a few years after the band’s start, as well as the requisite tales of album making, touring and excess. But a broader audience can find resonance in Raymonde’s telling of the distant relationship with his father, Ivor Raymonde, a musician, songwriter and arranger, a frosty connection that could be seen as distinctly post-World War II and distinctly British.

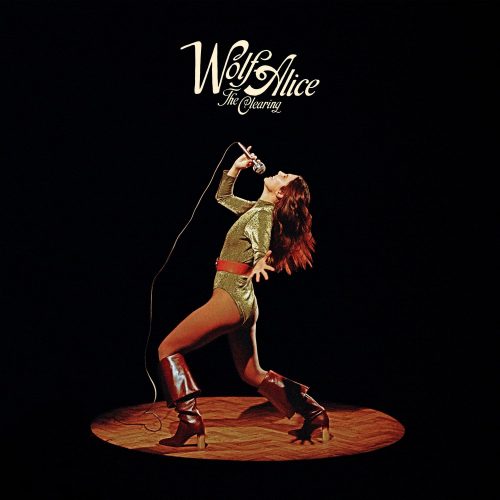

Raymonde, who founded Bella Union with Guthrie in 1997, in part to release Cocteau Twins’ music, has led the UK label to sign standouts such as Fleet Foxes and Beach House, a second career that gets its due in the autobiography and could be the subject of a second book, he says.

In advance of the North American publication of the autobiography on Nov. 18 and two New York City events — readings and signings at Rough Trade on Saturday, Nov. 15 and the Parkside Lounge on Monday, Nov. 17 — Raymonde chatted with us about his new perspective on Cocteau Twins thanks to the book and what helps him “escape the horrors of daily life.”

Did you reevaluate the Cocteau Twins’ legacy and the intraband relationships as you were writing the book?

I think so, to a great degree. When when you are almost 30 years away from something there is naturally a distance there that gives you a certain amount of perspective. I suppose I found it all quite fascinating and new and interesting and kind of dove straight into it with sort of gusto. When you’re doing something you’re maybe not quite aware of quite the meaning of it all. And so you sort of get close to the end and then you’re reading it back 500 times to check for mistakes, and then you’re moving this bit to that bit, and your knowledge of the book is just so intimate by the end. I’m sure you’ll know as a writer that you know a lot more at the end than you did at the beginning, not just about the book, but about yourself, about the events that happened and that, by its very nature, enables you to go, “You know, actually, that is really interesting.”

I haven’t really kind of appreciated quite how important this all was, and actually what a brilliant band this was to be part of, because you do get wrapped up in the minutiae of everything and the small detail and being annoyed about this little thing or frustrated about this little thing, which in the grand scheme of things is all nonsense and all irrelevant. And writing a book, I think you are able to to sort of throw away all of that uninteresting stuff that you know is not relevant and just focus on the music and the sort of legacy of what we did.

I thought it was interesting that you wrote about the lack of communication within the band, which paralleled the lack of communication with your dad. Did you feel like you were writing to them things you never got to say?

Yeah. I mean, the dad part for sure. There’s a really great question and I think maybe to the band, to myself, as much as anything, like making sense of it from my own perspective and almost kind of like saying to myself, “It’s OK that it was like this.” It wasn’t ideal. And certainly the situation of being in that band was peculiar. There’s no point pretending otherwise. It was an unusual band to be part of. And the circumstances of all of our lives at that particular time were quite unusual. So therefore it is going to be a moment in time that being older, being — whether mature, is quite the right word, I’m not sure, but being a bit wiser as to how people interact with each other and how that band was in the grand scheme of things — I am probably now more able to feel like I think I’ve addressed some things.

I feel like they’ll never read it. I’m absolutely sure about that. But if they ever did, perhaps they might understand my perspective a bit more. Not that that’s particularly relevant, and not that I care about it really, either. But if they did, it might certainly help them see the band slightly differently than I think we all must have seen it at the time, which was definitely through very confused eyes.

Why are you sure they’ll never read it?

I don’t know. I just can’t imagine they would. I think Elizabeth probably wouldn’t, because I don’t think that would be her thing, you know? Not for any bad reason, I just don’t think she would want to read a book about her own band. And Robin, because I think he has his own version of the Cocteau Twins’ story, which I know will be greatly different to mine. And I know that he he probably won’t want to read an alternative version. Yeah, I’m probably wrong. He’s probably read it five times and he’s making notes right now. I don’t know, but I don’t sort of lie awake at night worrying about it.

Of course, when I finished the book, I thought, what do I do, do I send it to them and check that they’re cool with it, because, you obviously don’t want anyone to sort of get a surprise and feel like, oh, you know, why are you saying that about me? But then the more I thought about it, I thought, well, I’m not throwing anyone under the bus here. This is just my version of events.

Has running Bella Union and looking for new music kept you energized about your own music and kept you more connected to music in general?

It’s probably a bit too strong to say it’s a reason for living, but it certainly gets me out of bed in the morning. That thrill of — I discuss it, I suppose, a little bit in the book — listening to Myspace back in the day and finding Fleet Foxes that way, or going to Texas and seeing Midlake or just walking into a bar with no one in it and five minutes later, you’re like, oh my God, this band is everything I’m looking for right now. So I do still have that, thankfully. I mean, the minute I don’t, I suspect every day when I get out of bed, that is it. Has it deserted me? You know, am I going to not be interested to listen to this link somebody sent me from SoundCloud or whatever? But I am always fascinated to listen because even though you might think, well, I’ve heard it all, haven’t I? Haven’t I heard everything by now, you know? You cannot have that attitude because you never have.

It sort of helps me get through the day by listening to a lot of music. I don’t end up doom scrolling on Instagram, just dreading everything in the world and reading horror news stories. And you know, I need to be connected to the world at some point, I guess. But music at least helps me sort of escape from the horrors of daily life.

This interview was edited for length.

Leave a Reply