By Greg Popil

There are many wonderful pleasures to being a filmgoer, but perhaps the greatest joy someone that really cares about movies can experience is the all-too-rare sensation of watching a movie (or series of movies) that by all logic should not work, and yet somehow inexplicably does. 1968’s Rod Serling-penned “Planet of the Apes” will always remain an untouchable classic, but its sequels varied wildly in quality until shrinking budgets and levels of interest left the series a hollow shell. An attempt at a reboot in 2001 resulted in Tim Burton’s worst movie to date (which is really saying something if you’ve watched “Alice in Wonderland”) and few people believed that another reboot starring James Franco was a good idea.

All of which is what made the critical and commercial success of “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” so stunning. Ignoring the original movie’s astronaut plotline, “Rise” remade the original series’ sequel/prequels as a story about well-meaning scientists who try to cure Alzheimer’s disease and end up simultaneously annihilating humanity and creating a race of super-intelligent beings to replace us. The newest sequel, “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes,” doesn’t have that sense of surprise, but it builds on the established world to create something truly epic.

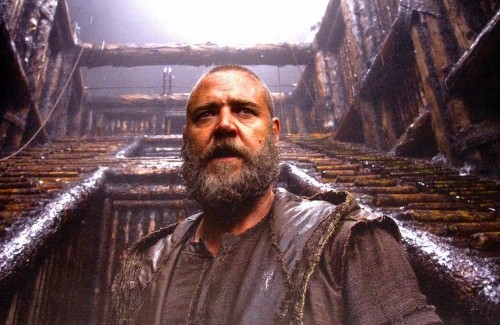

Ten years after the apocalypse (the opening sequence is chillingly quiet as it traces the spread of the pandemic), the apes, led by Caesar (Andy Serkis), have established a peaceful, near-utopian life for themselves, hunting, learning and raising painfully cute families together. Naturally, this peace is shattered, as the apes encounter a group of survivors living in nearby San Francisco, led by Malcolm and Dreyfuss (Jason Clarke and Gary Oldman). Caesar desperately wants to keep the humans away from the apes (many of whom share horrible memories of being trapped in human labs), but the humans are equally desperate to begin operating a nearby dam that would supply them power. The movie smartly balances these needs, never allowing the humans to slip into caricature or the apes to seem overly noble as a race. The metaphor of European pilgrims who desperately needed Native American help to survive is never far from the surface, but neither is it too overt.

For a while it appears that Caesar and Dreyfuss will be able to bridge the gap between the species, despite the best efforts of Dreyfuss’ trigger-happy friend Carver (Kirk Acevedo) and Caesar’s top lieutenant Koba (Tony Kendell). Koba is an astounding creation, a vicious, hate-filled creature, tortured for years by scientists, his body covered by scars that clearly go beyond the physical. Holocaust victim-turned-supervillain Magneto springs to mind. The “cute” antics that Koba uses to get close to a couple of gun-toting goons is simultaneously the movie’s funniest and scariest sequence.

Director Matt Reeves, working on only his third major feature, solidifies himself as one of the finest visual directors of the 21st century. Reeves is unafraid to allow several minutes to slide by without a single word of dialogue (the apes are haltingly learning human speech; most still communicate with sign language) and, in a rare move for a sequel, he devotes almost the entire first half of the movie to world-building and establishing characters, a necessity in a world where every human from the previous film has died. When the action starts, however, Reeves cuts loose. Reeves ditches the found footage angle of his feature debut “Cloverfield” but retains his eye for visual chaos. A scene where Dreyfuss scrambles to avoid capture recalls “Cloverfield’s” characters’ desperate attempts to survive apocalyptic destruction that rains from every direction, and an attack on a fortress late in the movie evokes no less an epic battle as “Lord of the Rings’” battle of Helm’s Deep. Reeves is clearly a student of Peter Jackson, as he allows small character moments to permeate even the largest of action scenes.

“Dawn’s” performances are universally fine: Reeves is a good stand-in for Franco as a representative of humanity’s better angels, as are Keri Russell and Kodi Smit-McPhee as his wife and son. Oldman’s role is underwritten, but that’s actually to the movie’s advantage, as he is not allowed to become the clichéd stand-in for humanity’s racism and hatred that one would initially expect. He doesn’t hate the apes, but he is also willing to do absolutely anything to ensure his people’s survival, and that trait is viewed exactly as heroically as it should be. But all the human performances live in the shadow of Caesar, and Serkis, a fine actor sans effects (check him out in Christopher Nolan’s “The Prestige”), continues to do for motion-capture acting what Mel Blanc did for voiceovers: carve poetry out of what could be a cheap effect. Should the Academy be daring enough to honor him with a nomination next year, he would have more than earned it.

Rating: 76/81

Leave a Reply