HARRISBURG, Pa. — If there is a perfect place to see Robyn Hitchcock, it would have to be in an intimate bar with décor favoring tasteful cartoon nudity and equipped with a stage bathed in pinkish light. Thankfully, the Stage on Herr in Harrisburg, where Hitchcock played last Wednesday, fits that bill to the T. Hitchcock is many things: the eclectic leader of neo-psychedelic rockers the Soft Boys, frontman of late ’80s college radio darlings Robyn Hitchcock & the Egyptians and a prolific and fascinating solo artist in his own right.

When Hitchcock took the stage on a Wednesday night in a bar packed with the sort of people who bought import records in the late ’70s, there was a complete hush and complete dimming of iPhones. This show was obviously something that many in the audience had been only dreaming of for many years, an evening with Robyn Hitchcock.

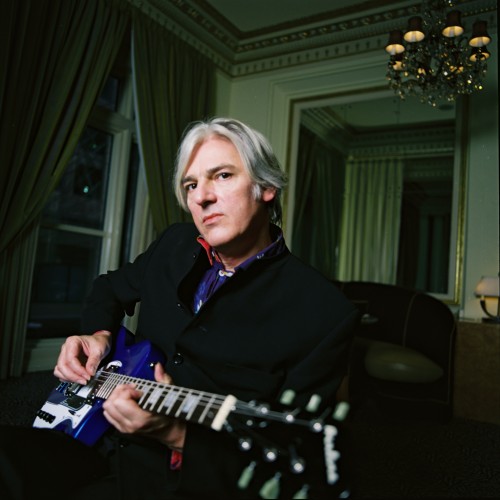

Hitchcock is an imposing figure, tall and lean, handsome in a perfectly off-kilter way even three and a half decades after the release of “Can of Bees,” the Soft Boys’ revered debut. Although famous for insane stage banter, Hitchcock started the show without a word, playing “The Abyss” from his 2011 album “Tromsø, Kaptein” accompanied only by acoustic guitar and harmonica, as though taking a reading on the his captive audience.

“Only the Stones Remain,” the tune Hitchcock miraculously decided to play next, is debatably one of his finest creations and one of the longest-standing works of the Soft Boys. The original is an aggressive, punk rock testament to mortality, a feat rarely approached by pop music. The rendition that Hitchcock played that night in Harrisburg only does the song more justice – his sneering vocals laid relaxed over the firm but unhurried strum of his guitar and the artful tension created in his perfect command of the stage. The slight but deliberate change in tempo and instrumentation seemed as though it could have been a reflection of Hitchcock’s growing acceptance and fascination with all of the things that the 2007 documentary about him, “Sex, Food, Death… and Insects” took its title from.

After a classic Soft Boys tune, it was obvious that Hitchcock had the entirety of the Stage on Herr in his palm, even the people who had decided to wander into the bar after paying the $25 cover charge without knowing anything about who was performing that night. Shortly after “Only the Stones Remain,” Hitchcock started making purposeful eye contact with people sitting throughout the space, everyone from the lovey-dovey couple in the corner of the room to the white-haired, enraptured pseudo-hippie lady sitting with her equally captivated partner in the middle of the audience.

After playing around 12 incredibly well-received songs, Hitchcock vanished behind the stage and came back out to introduce the audience to his “mother,” a rickety, naked female mannequin. Although the audience was palpably spooked that the set was over for good, Hitchcock soon came off of the stage with his guitar slung around his neck.

“I’m going to play you a couple of records from my record collection,” he said, before breaking out into a record store geek’s dream of covers. It was enough that he had covered Bob Dylan’s “Senor (Tales of Yankee Power)” during his main set – now Hitchcock was walking around the crowd, serenading everyone with “River Man,” a Nick Drake tune; “Dominoes,” a shout out to one of Hitchcock’s greatest influences, Syd Barrett; an exhilarating cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary”; and a triumphant and playful cover of David Bowie’s “Soul Love.”

If there was anything that diehard fans desperately wanted from Hitchcock’s performance that they did indeed receive, it was a series of impeccable reinventions of some of the classic pieces from Hitchcock’s highly diverse discography. “Madonna of the Wasps,” “One Long Pair of Eyes,” “Glass Hotel,” “Queen of Eyes” are just a couple of the songs that Hitchcock carefully lifted from his assorted projects, each one deftly rearranged to fit into his stripped down set.

The most amazing thing about Hitchcock is his ability to write songs that are all at once sinister, uncomfortably erotic and occasionally sweet – lyrics that can be boiled down to interpretations as varied as they are potentially jarring or soothing. “Death & Love,” a track from Hitchcock’s most recent effort “Love From London,” may not have been the track from the album that he chose to play in Harrisburg (that was a stunning version of the expertly crafted “Be Still”), but it does thoroughly describe something about what appears to be Hitchcock’s personal philosophy.

“Only one thing makes my heart beat faster and accelerates my breath/I can hear you talk my language/ talk the tongue of love and death” Hitchcock sings on “Death & Love,” a summary of what the artist speaks in, thinks in, writes in. Hitchcock is not only the oddball that gave the stink eye to his loving fans as he went offstage only to bring back a shaky female mannequin that he must have found backstage, only to explain to the audience that the mannequin was his “mother” and that she would be “finishing the show”; he is also the master of conveying the divinity and beauty that is inherently in the act of being alive.

Hitchcock is not reaching for some greater good with his lyrics or his art, and he never has been. He’s reaching inside of the human experience, all of the dirt and musk and unpleasantness that accompanies vital but messy bodily functions to create art that shows that being alive truly is enough.

Leave a Reply