My earliest memories of the Grateful Dead are me being confused as to why people loved them so much. I didn’t understand why, when I walked into a record store in Old Forge, Pa., on Aug. 9, 1995, the lights were off and candles were lit. I saw the news that Jerry Garcia died, and I knew he was important to millions of people, but it didn’t make sense. The store owner was inconsolable.

Not too long after, I remember walking to the bathroom to in my college dorm with a Creedence Clearwater Revival song in my head — I can’t recall which one. As I showered, I thought, why do people base their lives around the Grateful Dead and not CCR? CCR had just as many great songs. Why not Boston? Supertramp? I wanted to know what I was missing.

At some point that year I found myself in Mike’s Music & Movies just off campus. I was already a budding Phish fan and I was there to add their debut album, “Junta,” to my growing collection (at this point I had zero live tapes but the “A Live One” CD set was in constant rotation in my room and seemingly everywhere that year). Flipping through the used section, I saw “Skeletons from the Closet,” the Dead’s early greatest-hits album. I bought that one too.

When I spun “Skeletons,” I was immediately drawn to the Bob Weir songs — “Sugar Magnolia” (I heard the band Strawberry Jam play it at parties), “Truckin’,” “Mexicali Blues,” “One More Saturday Night.” Garcia’s “Casey Jones” was really good, too. For some reason the 1:58 trippy Garcia/Hunter piece “Rosemary” is on there, and I didn’t get it but I was intrigued. So I knew I liked the music, but it still didn’t “click” for me.

That’s because I hadn’t heard much of the Dead’s live material yet. And if I had, I’m not sure I would have been ready. That changed a few years later when I bought “Dozin’ at the Knick” (recorded March 24–26, 1990, at shows in Albany) at The Wall in the Wyoming Valley Mall and borrowed “One from the Vault” (recorded August 13, 1975, in San Francisco) from one of the guys in my fraternity house. From the opening roar of “Hell in a Bucket” on “Dozin’,” I was knocked out. The way Weir sang the Dylan covers “When I Paint My Masterpiece” and “All Along the Watchtower” was incendiary (I was yet to fully discover Dylan). The way “Playing in the Band” melted into “Uncle John’s Band” was unlike anything I had ever heard. How did they do that? And the warm “And We Bid You Goodnight” would often send me off to dreamland when I lugged my CD collection to England for a semester in 1998. “Vault” sealed the deal, with airtight, proggy jazz fusion, Keith Godchaux’s organ, Garcia’s guitar and Bill Kreutzmann’s drums weaving into something that was certainly beyond, and better, than rock ‘n’ roll.

That’s because I hadn’t heard much of the Dead’s live material yet. And if I had, I’m not sure I would have been ready. That changed a few years later when I bought “Dozin’ at the Knick” (recorded March 24–26, 1990, at shows in Albany) at The Wall in the Wyoming Valley Mall and borrowed “One from the Vault” (recorded August 13, 1975, in San Francisco) from one of the guys in my fraternity house. From the opening roar of “Hell in a Bucket” on “Dozin’,” I was knocked out. The way Weir sang the Dylan covers “When I Paint My Masterpiece” and “All Along the Watchtower” was incendiary (I was yet to fully discover Dylan). The way “Playing in the Band” melted into “Uncle John’s Band” was unlike anything I had ever heard. How did they do that? And the warm “And We Bid You Goodnight” would often send me off to dreamland when I lugged my CD collection to England for a semester in 1998. “Vault” sealed the deal, with airtight, proggy jazz fusion, Keith Godchaux’s organ, Garcia’s guitar and Bill Kreutzmann’s drums weaving into something that was certainly beyond, and better, than rock ‘n’ roll.

So I was in.

Next up was going to shows. The Dead were gone, obviously, but a close college friend and I made it from State College to Scranton in the summer of 1997 to see the Furthur Festival. We got there too late to see Bruce Hornsby (his show at the Kirby Center in Wilkes-Barre in 1995 was an eye-opener for me too, but I didn’t know his Dead lineage then) and moe. (already one of my favorite bands after hearing one of their albums at a party). Mickey Hart and his percussion ensemble, Planet Drum, was otherwordly. Arlo Guthrie’s songs and stories in between sets were the perfect interludes. And the highlight for me was Weir’s band, Ratdog: They opened (and closed?) with “Sugar Magnolia”! They did “Masterpiece”! And “Take Me to the River?” Wasn’t that a Talking Heads song?

I would go on to see most of the post-Dead outfits: Ratdog and Phil Lesh and Friends the most, but also The Other Ones, Furthur, The Dead and Dead and Co. I would have the opportunity to interview and meet Lesh a few years later when I was only 23. Weir recapped the end of a Patriots-Colts game for me and a friend — the same guy who went to Furthur festival with me — after a Ratdog show in State College. Another friend stepped on Weir’s foot after a show in Stroudsburg — we don’t think he noticed. The white whale of interviews for me was the publicity-shy Robert Hunter, Garcia’s lyricist. It finally happened a few years ago, as did a friendly hang before his show at the Kirby Center — where I had seen his old buddy Hornsby nearly 20 years earlier.

Getting to become acquainted with the members of the band on a very small level was exciting, but I’m glad it came after I was fully immersed in the music. That way it didn’t have the potential to change how I listen; it didn’t make me like it any more or any less.

It took me years to understand it, but I think what makes Garcia and the Dead’s music mean so much to so many people is because it is what you make of it. It invites you in but doesn’t tell you what do once you’re there: “It’s got no signs or dividing lines/ And very few rules to guide.” You have to put time and energy into the discovery process. And if it grabs you, you find other tunnels to follow: bootleg tapes, old setlists, books, new friends you met at shows or online, YouTube rabbit holes of old interviews and shows. For every minute you invest, you get a lifetime’s worth in return.

The music means something different to everyone who gets it. It brings us together, but like a great book or painting, it’s something you can dive into alone.

And it’s always there for you. As Hunter wrote and Lesh sang in “Box of Rain,” “Believe it if you need it/ If you don’t, just pass it on.” And for Jerry, who died 25 years ago today, eight days after his 53rd birthday, another line from that song: “Such a long time to be gone/ And a short time to be there.”

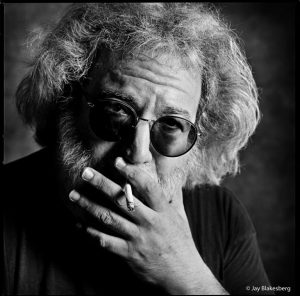

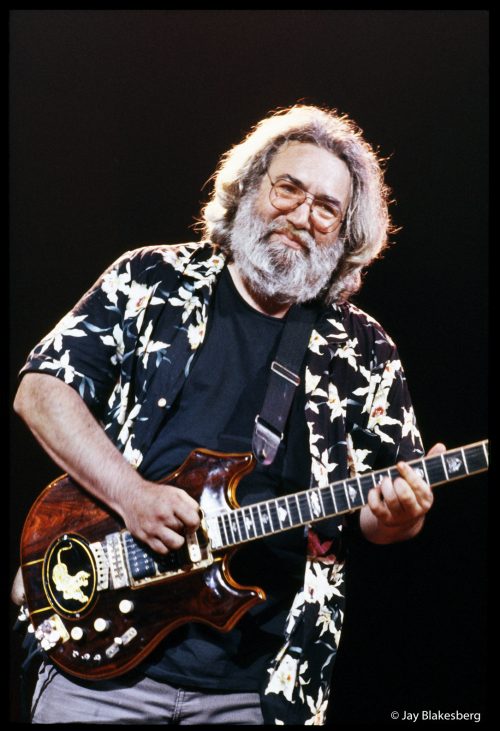

Photos courtesy of Jay Blakesberg from his book ” “Jerry Garcia: Secret Space of Dreams.”

Leave a Reply