By Greg Popil

A man, and a woman. A picturesque Missouri house, ripped from the pages of Better Homes and Gardens magazines. A marriage that seems like it should be the envy of the entire town. They’re both attractive, intelligent and urbane, and through flashbacks we can see their palpable chemistry, the way infatuation deepened into real appreciation and love (despite his adorably untrustworthy chin). But cracks are beginning to show. The man confesses as much at the bar he owns with his twin sister. He returns home later that morning to find his house upended and his wife missing.

The premise of “Gone Girl,” David Fincher’s adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s smash hit novel, wouldn’t sound out of place in the opening 10 minutes of a CBS procedural. Indeed, longtime fans of the director have muttered about how he is “lowering himself” to direct such a mainstream novel, seemingly devoid of subtext [note: I have not read said novel]. But Fincher is smarter and sneakier than that. One of the pioneers of conjuring high art out of the lowbrow medium of music videos, Fincher immerses himself in the story’s pulp trappings, and emerges with the year’s most penetrating examination of marriage and its pitfalls.

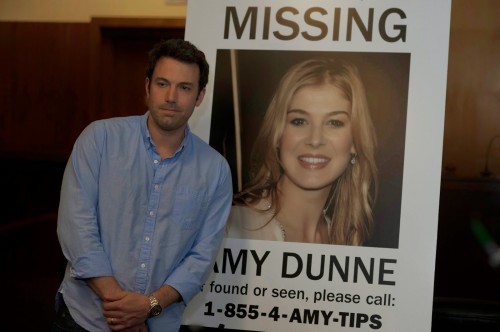

Playing with a non-linear timeline for the first time in his career, Fincher weaves the search for Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike), a Manhattanite trust fund woman living in Missouri, with flashbacks of her relationship with her husband Nick (Ben Affleck). We see them meet-cute at a party, flirt, fall into love, and desperately fight against the same growing cracks in their marriage that have affected millions of couples (income worries, questions of fidelity, relationships with in-laws), but they swear will never get to them. Fincher takes his time building these scenes, just as the local police (primarily represented by Kim Dickens and “Almost Famous’” Patrick Fugit) take their time building a case against Nick. Affleck, who infamously went through maybe the worst five years an actor could possibly endure from 2000-2004, is terrific here, saying all the right things in exactly the wrong way, his desire for privacy making him come off as cold and his awkward smiles in pictures attracting the ire of a Nancy Grace-esque reporter (Missi Pyle, who damn near steals the show with her infuriating sleaziness). The walls of the Dunne’s home slowly close in on Nick, to the point where he might be stuck inside Fincher’s “Panic Room” and even his loyal twin sister (Carrie Coon) is questioning his innocence.

At this point, although I will try to avoid specific spoilers, it becomes nearly impossible to talk about this movie without giving a few things away. Skip to the grade and read this after you’ve seen it if you would like to go in without knowing anything

There is, naturally, far more to the story than a simple murder, and although Fincher and Flynn (who adapted her own story for the screen) do an admirable job of making the truth about Amy at once horrifying and somewhat understandable. Amy’s parents (Lisa Banes and David Clennon) made their fortune selling an idealized version of their daughter as a children’s literature heroine, and Amy clearly feels an impossible pull to match the ideal of their “Amazing Amy.” Pike, an actress that I’ve never noticed in anything before, is breathtaking here, a Hitchcock blonde that can be sinister without resorting to tics or entirely losing the audience’s sympathy (her heartbreak over Ben’s dalliances with a younger woman are the most poignant scenes in the film). Even as Affleck attempts to right the ship and turn the case in his favor, by doing interviews, hiring a slick lawyer (Tyler Perry, surprisingly funny) and tracking down Amy’s oddball ex boyfriend (Neil Patrick Harris), you can see Amy is several steps and IQ points ahead in the game.

This is a story tailor-made for Fincher and his infamous, Kubrick-style perfectionism, one where careful, intricate planning is rewarded and impulsive decisions, either a passionate affair or a celebratory jump in the air, is punished. Fincher has long earned his place in the Horrific Cinematic Violence Hall of Fame, but like “Zodiac” he uses it sparingly here, so that the single instance of domestic violence and the single onscreen death come as real shocks. But the shock of violence is nothing compared to the paranoia and anxiety that the leads feel at the idea that their lovers’ true thoughts and plans are unknowable. “Who are you?” they ask each other in their first meeting, and the tragedy of “Gone Girl” is that they are never able to stop asking that question.

Rating: 76/81

Leave a Reply