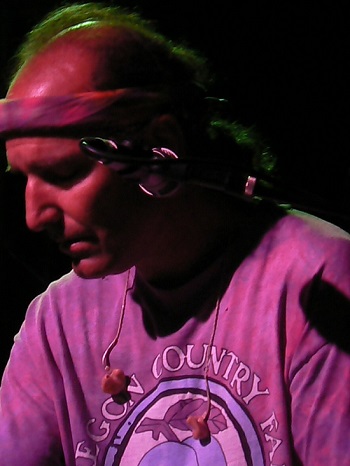

Late last year, we spoke with Rob Barraco in advance of a few Mattston/Barraco & Friends performances. Inevitably, the conversation with Barraco – a pianist, keyboardist, occasional bassist and vocalist known for his work in post-Grateful Dead groups like Dark Star Orchestra, Phil Lesh & Friends and The Dead – shifted to his early impressions of the Dead. In the spirit of the Dead’s 50th anniversary and career finale “Fare Thee Well” concerts in Chicago this weekend, we’re now sharing the portion of the interview that relates to the iconic group founded in 1965.

What impact did the Grateful Dead have on you as a youngster? What turned you on to the band?

Well, I mean there are a couple of those milestones along the way. The first two things that happened to me, when I was 15 I saw the Allman Brothers for the first time. It was my very first concert I went to at CW Post on Long Island. It was the very first show after Duane [Allman] had passed, and the sheer power of it is what really got me, it hooked me to want to play live music.

But four months later I got to see the Grateful Dead for the first time in New York City, and that was a life-changing experience. Phil Lesh, listening to him play bass really changed my perspective on what music was about. There is nobody that does what he does, and nobody ever will, in my estimation. So that night, I set on my path, more or less. I knew what I wanted to do, where I wanted to go, never ever thinking that I’d end up playing with those guys. But it definitely set the stage for me to want to get into improvisational music at that level. And then of course that led me very smoothly into the jazz world. I just loved improvisational music and the conversation you could have as musicians. Those are the two defining moments of my early life that set me on a career path.

With DSO, your job is to recreate the different styles of the Dead’s various keyboard players depending on what original concert you are recreating. Which of those keyboardists is closest to you stylistically? And what are the biggest challenges of switching from one player’s style to the other from night to night?

Without a doubt, Keith Godchaux’s piano playing is the closest to what I aspire to as a player. He had a jazz background, he brought that jazzy thing to the Dead that they never really had before. Now, the challenge for me up there is by the late ’70s I kind of got out of the Dead scene. I wasn’t enamored with the band’s direction, the graduating into playing stadiums and the big, huge rock production, it didn’t appeal to me so much. Now I grew up in an era when the Dead were playing in theaters and smaller college gyms and stuff. I just thought that the music had lost some kind of direction. I don’t know if it was because the band didn’t seem to be as connected to me. I since have been proven wrong, because with Dark Star I had to look back through the catalog and listen to a lot of the ’80s stuff, and I realized that I actually missed out on a lot of pretty good music. And I was on a different career path at that point. I really adopted to the jazz world and that’s what I was studying.

The biggest challenge for me when we recreate ’80s shows, to do the Brent Mydland thing, I wasn’t that familiar with it. As a singer, it improved my singing 100 percent. I’ve had to take on the role of the high harmonies. I’m really grateful, no pun intended, to have the opportunity to have done that because it’s made me a much better musician. And the other challenge is learning the different arrangements from the different years in Dark Star, and then I have to go play with Phil and have a different arrangement, and then coming back to Dark Star, it starts to swirl in your head (laughs).

Do you feel that the fact that these songs are able to stand up to so many different arrangements over the years proves how strong and versatile the songs were in the first place?

Oh, absolutely. Phil always said that Grateful Dead music should be a repertory, it should be performed by everybody however stylistic way they want to, it will hold up. Phil has changed some of the tunes so drastically over the years, and they still hold up, they’re still cool. I think sometimes the audience looks at you like “Whoa, what are you doing?” But, for me, I look at it, it still works. If you’re doing “Fire On The Mountain,” “Fire On The Mountain,” whatever you do to it, it’s still “Fire On The Mountain.” That chorus is so strong. And take artists like Dylan. Dylan morphs some of his tunes to the point they were unrecognizable. When you first hear them, you’re sitting there going “what the hell song is this?” and then you get to the chorus and you can’t deny what song it is.

Phil continues to rotate the Phil Lesh & Friends lineup, but the “Quintet” lineup – Phil, Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring, John Molo and you – stayed together for a while and played a reunion show at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens last year. What is it about that lineup that makes it so special to the fans and the band as well?

We have a rapport together, the five of us, that is unparalleled, at least in my estimation. Of all the bands that I’ve ever been in, I’ve never had that kind of connection, musically, spiritually. When Warren and I sing together there’s a blend there that I’ve always wished I’d have with anyone else I sing with, but that’s the best I’ve ever had.

Did you have any interactions with Dylan when you played shows with him? There are a lot of stories out there about people playing on entire tours with him and never meeting him.

Well, first of all in the fall of ’99 we [Phil & Friends] co-billed with Dylan, and I always hear that you’ll never get to see him. So for me it was really special. I got to do 13 Dylan shows, and that’s where I experienced him changing tunes and not even knowing what they were until the chorus, and then it was, “Whoa, I can’t believe that’s ‘Blowin’ In The Wind!’” or whatever. It was cool meeting him. He’s got that voice, it’s almost like he’s singing to you: “Hi, nice to meet ya.” He’s an interesting character, I’ll tell you what. It must be very interesting trying to be Bob Dylan, like trying to go out in public; everybody knows who you are, there’s not a single person that you could fool.

Leave a Reply