It doesn’t take long to become wrapped up in the glossy genre gymnastics of “Pony.” “Dead of Night” kicks off Orville Peck’s Sub Pop debut with a simple guitar that is both sonically and melodically reminiscent of “Twin Peaks,” and the chorus allows his voice to soar into a falsetto that shouldn’t be physically possible given his erstwhile baritone singing voice. The song then ends with a banjo coda that wouldn’t be out of place in one of the late-summer/early-autumn folk jams that are the stock-in-trade of labelmate Iron & Wine, and the sum of all these parts suggests Peck as a country singer with a new and invigorating artistic perspective for the genre. It turns out that this opening track is merely the first surprise in an LP full of them.

The album has more than its fair share of chugging prairie travelogues (“Winds Change,” “Turn to Hate,” “Buffalo Run”), each more revelatory than the last, cutting a character out of whole cloth who is not detached, per se, but is unattached to anything. The listener is never sure whether the lack of attachment is due to circumstances or conscious choice, but it may not matter. Peck has mastered the musical embodiment of an archetype inherent in some of the best country music and Old West films, that of the solitary drifter. He is the kind of lone wolf that rides into town with no name and is inexplicably gone one morning, an already fading memory and a faint scent of smoky leather the only evidence he had ever been there at all.

When not kicking up dust on the trail, the masked man shows a penchant for an operatic and vaguely spiritual sense of barn-burning catharsis that goes well past the rafters and defies the impersonal sky itself. The nearly a cappella “Old River” plays like a chain gang work song but speaks of the pain and unresolved mystery of a specific loss (“…sister broke her crown…each small bullet makes a sound”). His “Queen of the Rodeo” is a woman living through a fable of society collapsing in on an individual, and Peck drops some of the lyrical obscurity here when he relates to her with the simple but powerful line “this world is a bummer.” She is a character behind smeared glass, clear as a symbol but lacking in detail, and while Peck may not fully understand her situation he can clearly relate to the idea of being scapegoated and/or bullied. That context makes it all the more telling when, in the same breath, he also advises her to not let it get her down.

Reference points aplenty allow us to get our footing. Beyond the tremolo bursting through the syrupy guitars and the occasional use of a gated reverb that points to a keen reverence for ’80s rock (“Hope to Die”), Peck also tips his hat to Ritchie Valens’ legendary “Sleepwalk” on “Roses Are Falling” and offers a slow dance floor-filler that could become a standard for both high school proms and wedding receptions in the flyover states. His Elvis-tinged vocals here are a nice touch, as well — it turns out that the nameless stranger shares some of our cultural history after all, and ironically that only serves to make him that much more of a riddle. On “Take You Back (The Iron Hoof Cattle Call),” he gives himself over to a whistling melody, whip cracks and a cocky bravado that calls to mind both Johnny Cash’s glory days and the theme songs to TV Westerns.

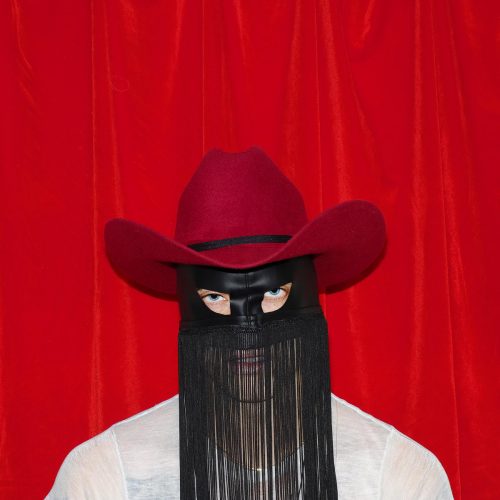

“Pony” is full of sensual music that is both tacitly suggestive and utterly absorbing; it weaves back and forth like a snake charming its own charmer, and in doing so it becomes an abstraction covered in equal parts glitter and dust. Peck is a tour guide for those that have been marginalized by the mainstream as they navigate the terrain of a country music that feels unmistakably new and wholly more inclusive. His persona here, masked and nearly anonymous, is one that completely earns his swagger throughout the song cycle and makes repeated listens rewarding on multiple levels. But that’s the other thing about the lone drifters that populate Western movies: They always leave us wanting more.

Rating: 69/81

Leave a Reply