In the 1960s, the idea of what it means to be an American was changing. As a war raged in Vietnam, protests raged at home. Young people were no longer accepting that whatever their parents or government was telling them was in their best interests. Against this backdrop, great art was flourishing, from Andy Warhol to Bob Dylan.

Elliott Landy, born in the Bronx in 1942, was drawn to the culture of protest and collaborated with his camera. Landy’s work documenting the protests in New York City for the underground press led him to the adjacent music scene, and his work photographing artists such as Bob Dylan, The Band and Janis Joplin, now serve as a historically important archive of those pivotal times. Among the images he captured include the cover of Dylan’s “Nashville Skyline” album (shot in Woodstock, not Nashville) and the pictures in The Band’s debut, “Music From Big Pink.” He also served as the official photographer of the Woodstock Festival in 1969.

Living in Woodstock since the 1960s, Landy is about to publish his second volume of photos of The Band, the group of mostly Canadian musicians who settled there as well. The Kickstarter for the project is entering its final week.

“After I did my first book, ‘Woodstock Vision,’ in 1999, I wanted to do a book of my Band photographs because that was my best photographic work from that period,” Landy said in a recent interview with Highway 81 Revisited. “And with the discord between the guys in the band, Robbie [Robertson] and everyone else really, and especially with Levon [Helm], I’m thinking, how do I do this? How can I, it’s not right. It’s fighting with each other and I won’t want to get in the middle of it. And then I was in the south of France in July for a photography festival there, and I woke up one morning dreaming of a photograph of The Band.

“So I was dreaming of a photograph of them sitting on the lawn of a house that Garth [Hudson] and Richard [Manuel] were sharing, and they were all sitting on the lawn. Garth was standing up playing a standup bass, and it was like a perfect spring, early summer day. The super bright, super bright green grass and everything was totally mellow and peaceful. It was like perfection. And these five guys were sitting with instruments playing them, nobody was posing for the camera. They were just into playing their instruments. And there was some art instruments also. It wasn’t all standard classical instruments. So I realized that that was the theme of the book.”

The Kickstarter that Landy launched to fund the production of his first Band book was, at the time, the highest-funded photographic book in the platform’s history, he said, adding, “I was really surprised that did so well.” A few years later, he found boxes of prints of photos that were not used in the book.

“I opened it up and I looked at them and I see, wow, that picture’s not in the book. And I couldn’t believe that some of these really great photographs were not in the first book. And then of course there wasn’t enough space. And I said, I can’t imagine why I left that one out. It was on that level. So at that point I decided that I would have to do a second band book because there are so many good photographs. And it’s not like there’s seconds, or when you hear an album of outtakes that the music that you hear is not as to my opinion for most of what heard substandard not as good as the original. In this case, they’re really great photographs and they belong in the book also.”

Landy was initially connected to The Band by Albert Grossman, their manager, who was also managing Dylan and Janis Joplin. During their first run-in, Grossman had Landy thrown out of a Dylan concert that he was photographing even though he had a press pass. The next interaction came at a show by Big Brother and the Holding Company, Joplin’s band, at a club called Generation, which would become Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady studio.

“I feel a tap on my shoulder as I’m taking pictures. And it’s Albert. And I didn’t know if he was going to throw me out or what because he had thrown me out of Carnegie Hall before that,” he said. “But we had some interaction in his office, but it definitely wasn’t a smiley positive thing. He was letting me photograph Janis because it was an assignment for a magazine. So he takes me back where we could talk, and we went into a utility closet and he said, ‘Are you doing anything next week? Are you free this weekend?’ So I said, ‘No, I’m free. Why?’ He said, ‘Well, we have a new band.’ And I said, ‘Well, what’s their name?’ And he said, ‘We don’t have a name yet. Maybe The Crackers. But they’re also thinking of not having any name, because they don’t want to be pigeonholed into a certain kind of music. They want to be free to experiment and explore and change what they do. So we don’t even know if they’re going to have a name. And right now we haven’t decided on one.’ So that was the group that is now known and was known as The Band.”

His first shoot for the band was in Canada, “because they wanted to pay homage to these people who had raised them and helped them grow into who they were.”

“Now in the ’60s, since the culture needed changing so much that the people that were against the culture, the hippie generation and anti-war activists, dismissed their parents and their family because they were part of this overall culture that really was a breeding ground for war,” Landy said. “So people were kind of dismissive of their parents and not paying attention to them, not staying in touch with them and so on. And the guys in The Band were saying, ‘Hey man, look, they gave their lives to you and they love you and they made you who you are. They enabled you to be who you are.’ That’s why they were taking pictures of their relatives in Canada, because they all came from Canada except for Levon. So then a few weeks after that, those pictures came out nice. And then a few weeks after that they asked me to come up to where they were living and playing, which turned out to be what we know as the Big Pink House right in Woodstock, New York.”

Landy went on to shoot Dylan at his home in Woodstock, and he describes an easy relationship with Dylan that goes against the singer and songwriter’s mercurial reputation.

“At one point I met Dylan at a party, just a very quick introduction. And the album, “Music From Big Pink,” the photograph came out quite well. And maybe a few months after that I got a call from a journalist named Al Aronowitz, who’s a friend of The Band’s and a friend of Bob Dylan. And he said that Bob needed a picture for the cover of the Saturday Evening Post and would I come up and take one of Bob, just like that. And so then I became very close with Bob at the time, actually very close. I mean, we talked for a long time about a lot of stuff. And he asked me, he invited me to take pictures of him with his family, which no one else has or had done at the time. And maybe the reason that I was allowed to do that in a way was that it didn’t mean anything to me other than taking photographs of a very happy family, happy children, and the parents were just loving each other clearly and loved to be in the family space. So that was what my thrill was, the actual picture itself, not the celebrity of who was in the picture.

“And that’s why I was able to get close to Dylan and the people in The Band and whoever else who was famous I photographed in those years. Because for me, I was just in it for the picture. My desire, my job was to make a beautiful photograph, and that was the first thing that they would like. Also, it was a collective collaborative. It was a collaborative situation always for me. And also, I never pushed people around. When I photographed them, I let them be who they were, do what you want. The first time I photographed Dylan, Aronowitz introduced us, and then he got back in his car and drove away. And there I was like 10 feet away from the most famous guy in the world as far as I was concerned, a great musician who was doing a lot to change the nature of the culture and society and to help end the war with his music.”

Landy explained that because he was “just in it for the picture,” he eventually walked away from music photography.

“There’s no emotions, there’s no neurosis, there’s no desires to make money. No ‘where am I going to sell these pictures’ and stuff like that,” he said. “As a matter of fact, the reason why I stopped music photography, I did very well very quickly with ‘Music From Big Pink’ and ‘Nashville Skyline’ and Van Morrison’s ‘Moondance,’ and then the second Band album. And then I didn’t want to do that kind of photography anymore, and I realized that was because I had done it already. I didn’t see myself as an artist [at that time], I never wanted to be an artist. I never wanted to be a photographer. I wanted to take pictures. But the a priori definition of art is that it’s new and it’s different and it’s not the same as what’s happened before, and I realized that internally I was an artist. I realized it many years later. I wasn’t interested in photographing musicians and the whole culture that went along with it because I had done it already there.”

Landy said his next book will be photographs he has taken of his wife over the past 20 years, and he plans to call it “Love At 60.”

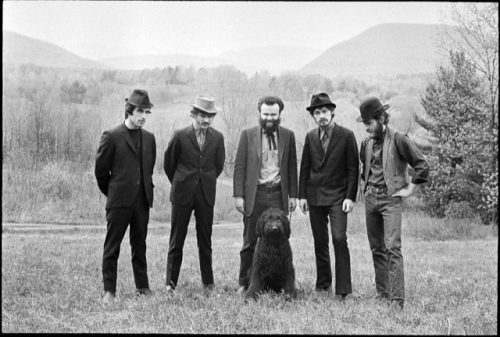

Lead photo: “The Band with Hamlet, Woodstock, NY, 1968 ©Elliott Landy”

Leave a Reply